Facial Trauma

Introduction:

Facial injuries could involve soft tissues, bones or even both. Majority of these injuries are caused by:

Automobile accidents

Sports injuries

Fights

Assaults

Management of facial injuries involve

General management

Soft tissue injury management

Bone injury management

General management:

This include:

Air way management:

Air way maintenance should be the top priority. Obstruction of airway could be caused by loss of skeletal support to the trachea, aspiration of foreign bodies, aspiration of blood or gastric contents, swelling of soft tissues causing airway compromise. Air way is secured by intubation / tracheostomy.

Bleeding:

Facial tissues are highly vascular in nature. Hence injuries involving the face could bleed profusely. Face bleeds can be stopped by applying pressure / ligation of bleeding vessels.

Other associated injuries:

Facial injuries can also be associated with injuries involving head, neck, chest, abdomen, larynx, cervical spine, limbs. These injuries should be attended to without any delay.

Soft tissue injuries and their management:

Soft tissue injuries of face may or may not have associated fractures of facial bones. The aim of management is functional and aesthetic recovery in the shortest period of time. Many of these patients would reach the casualty after having undergone incorrect approximation of soft tissue, or randomly applied single layer of deep stitches with misaligned tissue. A varitey of foreign bodies and unnoticed hematoma could complicate the situation.

It should be stressed that the first chance is the best chance for repair of facial soft tissue injuries. Surgeon embarking in these repairs should have a clear understanding of wound healing biomechanics, biochemistry, molecular biology of wound healing and art of soft tissue repair. It should be pointed out that many facial malformations in adults can be attributed to early childhood trauma. Early childhood trauma has deleterious effect on the growth and development of facial bones.

Evaluation:

Facial injuries are rarely life threatening. Types of soft tissue injuries include:

1. Abrasions

2. Tattoos

3. Lacerations

4. Contusions

5. Avulsions

6. Bites

7. Burns

Etiology of soft tissue injuries to face:

RTA

Gun shot injuries

Blast injury

Foreign bodies

Homicidal trauma

Thermal burn

Electrical burn

Clinical features:

They include:

Ecchymosis

Oedema

Subconjunctival hemorrhage

Crepitus

Hyperaesthesia

Facial nerve palsy

Inadequate excursion of muscles of facial expression

Inadequate excursion of muscles of mastication

Horizontal injury across the face could damage more vital structures than a vertical injury as it passes through more number of zones. The following are the aesthetic units of the face:

Frontal

Temporal

Supraorbital

Infraorbital

Nasal

Zygomatic

Buccal

Labial

Mental

Parotid - Masseteric

Auricular

In deep injuries of face, commuication with oral cavity, nasal cavity and maxillay and frontoethmoid sinuses should be looked out for.

Emergency management:

1. Airway compromise should be identified / anticipated and managed

2. Foreign bodies (broken teeth, and bone fragments can be mechanically removed by finger sweep technique

3. Airway compromise:

Can occur due to floor or mouth / tongue base support loss due to communited mandible fracture. This can be alleviated by traction of the mandibular symphysis. Falling tongue should be pulled out using an atraumatic forceps. Tongue base odema causing laryngeal obstruction is an indication for emergency tracheostomy.

Bleeding:

After control of bleeding volume resuscitation should be performed.

Soft tissue injuries do not need special diagnostic study. Radiographic evaluation could identify presence of foreign material, presence of facial bone fractures.

Management principles:

The face consists of several prominent zones and organs (Ear, Eyes, nose, lips, chin, cheek, forehead etc). It should be realised that when there is a composite full thickness loss of tissue it needs to be lined to provide cover and support for eye lids, nose, ear and cheek. Damaged upper eyelid should be reconstructed to avoid exposure keratitis.

Many facial wounds would at first sight suggest significant tissue loss. Careful replacement of tissue would reveal that majority of tissue mass is still present making repair really worthwhile. Many avulsed / amputated portions of the soft tissue are amenable to replantation.

Wound cleansing:

Facial wounds should be throughly cleaned off any dirt, grease or FB. Lacerations can be closed by accurte approximation of each layer of the tissue.

Parotid gland tissue:

Parotid gland tissue if exposed due to injury should be repaired by suturing. Injuries to parotid duct is considered to be more serious. Both ends of the injured duct should be identified and sutured over a polyethylene tube with fine sutures. The tube should be left in place for 3 days to 2 weeks.

Facial nerve injuries:

If facial nerve is severed, it should be fully exposed after performing superficial parotidectomy and the cut ends of the nerve should be approximated with 8-0 or 10-0 silk under magnification.

Periorbital & Frontal injury:

In these patients the eyelids should be inspected for the presence of:

1. Ptosis - suggests presence of levator apparatus injury

2. Rounding or laxity of the canthi - suggests canthal injury / naso-orbital-ethmoidal fracture.

In the presence of periorbital injury, it is important to judge the integrity of levator palpebrae superioris, orbicularis oculi an frontalis muscles.

Any injury near the eye should alert the physician to perform complete ophthalmological examination including tests for visual acuity, diplopia and evidence of globe injury. Orbital rims should be palpated to rule out fractures (to look for step deformity). The condition of eyelids, and integrity of both medial and lateral canthi are to be tested.

The integrity of supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves that supply sensory innervation to forehead and scalp should be tested by testing sensation in these areas.

Laceration injury involving lid margins require careful closure to avoid lid notching and misalignment. Initially key stitches using 6-0 proline are put in the lid margin to align with the grey line and lash line. These sutures are kept untied till the conjunctiva and tarsal plate are repaired. Then the skin sutures can be placed. Avulsive injuries to the lids can be treated by post auricular full thickness skin graft. Laceration involving the medial third of the eyelid may cause canalicular injury, which can only be indentified using a magnification loupe. If the proximal end of the canaliculus is not found then a lacrimal probe may be inserted via the punctum and passed distally out of the cut end of the canaliculus. The distal end of the canaliculus can be identified by introducing a pool of saline in the eye. Presence of bubbles would reveal the location of the distal canalicular stump. The canaliculus can then be repaired over a silastic or polyethylene lacrimal stent using absorbable 8-0 sutures. The stent must be left in place for 2-3 months.

Injury to nose:

Nose is prone to injuries due to its prominent position in the face. While examining such patients, the external covering, framework and lining of the nose should be carefully considered. The external soft tissue is assessed for lacerations or loss of soft tissue. Nasal framework can be assessed by asymmetry or deviation of nasal dorsum. Fractures involving nasal bones can be suspected due to deformities, presence of crepitus and radiological evidence of fracture. Cartilaginous injuries can easily be seen through the open wound. Speculum examination of interior of nasal cavities would reveal mucosal lacerations, exposed cartilage, exposed bone, or the presence of septal hematoma. If cribriform plate is fractured then there will be associated CSF leak which could present as watery discharge through the nasal cavity.

Nasal lining should be repaired with 5-0 catgut. In septal fractures if lining is present on one side then it does not pose significant problems. Cartilage lacerations should be repaired with non absorbable 5-0 sutures. Loss of support structures should be reconstructed immediatly using bone / cartilage grafts. Skin of the nose is repaired by placing key sutures at the rim of the nose using 6-0 poliethylene before residue closure. The skin over the tip and ala of the nose is adherent and less mobile and hence defies primary closure. Post auricular full thickness skin graft could be used.

Injury to ears:

This is rather common because of the prominence of pinna in the face. Examination of pinna should be performed to rule out any loss of tissue. Cartilage injury should be assessed. External auditory canal should be inspected for injuries as it could cause stenosis. The preauricular area should be assessed with great care as this tissue could be used for tissue repair.

Important concerns as far as pinna injury are hematoma and chondritis. Hematoma if present should be evacuated as quickly as possible to prevent cartilage resorption which could lead to deformity of pinna. A bolster dressing is advisable to prevent reaccumulation of hematoma. IF one surface of the cartilage has skin covering then it sould definitly survive.

Cheek and oral cavity injury:

In lacerations involving cheek the phycisian should carefully look for injury to the branches of facial nerve and parotid duct. In deep wounds there is a possibility of damage to multiple muscles. The oral cavity should be inspected for the presence of loose / missing teeth. Evidence of injury to mucosa, submucosa and presence of sublingual hematoma should be watched for. In the presence of intraoral injury, the muscle and overlying mucosa can be approximated as a single layer or individually. Care should be taken to separately reapproximate the underlyling orbicularis oris muscle.

Wounds that cross the line from the tragus to the oral commissure should be viewed as potential injury to the parotid duct. In suspected cases of injury to parotid ducts, a 22 gauge catheter is inserted intraorally to cannulate the stenson duct and a small quantity of saline is injected. Egress of fluid from the wound would confirm parotid duct injury. If the parotid duct is divided the two ends should be identified and repaired over a fine stent. Laceration injury to parotid gland without injury to parotid duct could result in sialocele. It usually gets sealed by repeated aspirations. If only the gland is injured then overlying soft tissue is repaired with a drain.

Fractures involving upper third of face:

Frontal sinus:

Frontal sinus fracture could involve anterior wall, posterior wall or the nasofrontal duct.

Fractures involving anterior wall of frontal sinus:

This could be depressed / comminuted. Defect is usually cosmetic in nature. Sinus can be approached through the skin wound if present or via a brow incision. Non displaced fractures ( less than 1-2 mm) can be observed with little risk of long term complications. Fractures with displacement greater than (2-6 mm) present little risk of mucocele formation. The bone fragments can be elevated taking care no to strep their periosteum. The interior of the sinus should always be inspected to rule out fractures of posterior wall of frontal sinus. If scar needs to be avoided then bicoronal flap approach is preferred to enter the frontal sinus.

Posterior wall fractures:

This fracture could be accompanied by dural tears, brain injury and CSF leak. These patients require neurosurgical consultation. Dural tears should be covered by temporalis fascia. Smaller openings can be obliterated using abdominal fat.

Nasofrontal duct injury:

This could cause obstruction to frontal sinus drainage into the nose. This could lead to later mucocele formation of frontal sinus. A large opening is created in these patients to enable the frontal mucocele to drain into the nasal cavity.

Anatomically the frontal sinus is protected by a thick cortical bone and is more resitant to fracture than any other facial bone. Fractures involving frontal sinus is rather rare.

Fractures involving supraorbital ridge:

Supraorbital ridge fractures can cause periorbital ecchymosis. There is flattening of the eyebrow, proptosis / downward displacement of eye. Bone fragments can also be pushed into the orbit causing impaction. Ridge fractures usually require open reduction through brow incision.

Fractures of middle third of face:

This involves nasal bone fractures and fractures involving nasal septum.

Nasoorbital fractures:

This is caused by direct force over the nasion. This causes fracture of nasal bones with posterior displacement. Fracture also involves perpendicular plate of ethmoid, ethmoid air cells and medial wall of orbit.

Clinical features:

1. Telecanthus - This is caused due to lateral displacement of medial orbital wall

2. Pug nose - Bridge of the nose is depressed and the tip is turned up

3. Periorbital ecchymosis

4. Orbital hematoma due to bleeding from anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries

5. CSF leak due to fracture of cribriform plate of ethmoid bone

6. Displacement of eye ball

Management:

Closed reduction:

Uncomplicated cases can be managed by close reduction using Ash forceps. Bones can be stabilised by passing a wire passed through fractured bony fragments and septum. It is tied over the metal plates. Intranasal packing is usually given.

Open reduction:

This is useful in cases with extensive comminution of nasal and orbital bones. Nasal bones can be reduced under vision and the normal height of nasal bridge is achieved. If bone comminution is severe, restoration of medial canthal ligaments and lacrimal apparatus should receive preference over reconstruction.

Fracture zygoma (Tripod fracture):

After nasal bones zygoma is the second most frequently fractured facial bone. This is usually caused by direct trauma. This results in flattening of malar prominence and step deformity at the infraorbital margin. Zygoma is seperated from its three processes. Orbital contents could herniate into the maxillary sinus.

Clinical features:

1. Flattening of malar eminence

2. Step deformity of infraorbital margin

3. Anesthesia over infraorbital nerve area

4. Trismus

5. Oblique palpebral fissue due to displacement of lateral palpebral ligament

6. Restricted ocular movements due to inferior rectus muscle entrapment

7. Periorbital emphysema - This is caused due to escape of air from the maxillary sinus due to nose blowing

Blow out fracture:

This involves fracture of the floor of orbit with prolapse of orbital contents into the maxillary sinus.

Fracture maxilla:

Facture maxilla is classified into three types:

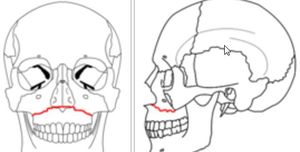

Le Fort I fracture:

Fracture runs above and parallel to the palate. It crosses the lower part of nasal septum, maxillary antra and the pterygoid plates.

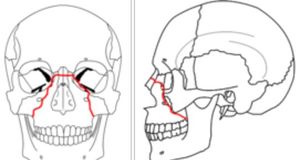

Le Fort II (Pyramidal fracture):

Fracture passes through the root of the nose, lacrimal bone, floor of orbit, upper part of maxillary sinus, and pterygoid plates. This fracture has some features common with zygomatic process.

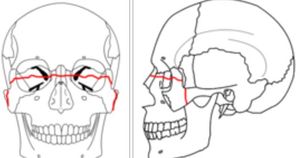

Le Fort III (Craniofacial dysfunction):

In this type there is complete separation of facial bones from the cranial bones. The fracture line passes through the root of the nose, ethmofrontal junction, superior orbital fissure, lateral wall of orbit, frontozygomatic and temporozygomatic sutures and the upper part of pterygoid plates.

Clinical features:

1. Malocclusion of teeth with anterior open bite

2. Midface elongation

3. Mobility in the maxilla

4. CSF rhinorrhoea. Cribriform plate is injured in Le fort II and III fractures.

CT imaging is diagnostic.

Treatment:

This is highly complex. Immediate attention should be paid to restore the airway and stop hemorrhage from maxillary artery or its branches. For achieving better cosmetic results these fractures should be treated as early as the patient's condition permits. Associated intracranial and cervical spine injuries may delay treatment.

Fixation of maxillary fractures is achieved by:

1. Interdental wiring

2. Intermaxillary wiring using arch bars

3. Open reduction and interosseous wiring as in zygomatic fractures

4. Wire slings from frontal bone, zygoma or infraorbital rim to the teeht or arch bars.

Fractures of lowre third of face:

This involves fractures of mandible. Fracture mandible have been classified according to their location. Condylar fractures are the most common. Other types of fractures involve fractures of the angle, body and symphisis. Fractures of the ramus, coronoid and alveolar process are uncommon. Most of these fractures are the result of direct trauma. Displacement of mandibular fractures is determined by the pull of muscles attached to the fragments, direction of the fracture line and the level of the fracture.

Clinical features:

In fractures of condyle if fragments are not displaced, pain and trismus are the main features. Tenderness is elicited at the site of the fracture. If fragments are displaced, there is in addition malocclusion of teeth and deviation of jaw to the opposite side on opening the mouth. Most of the fractures of the angle, body and symphysis can be diagnosed by intraoral and external palpation. Step deformity, malocclusion of teeth, ecchymosis of oral mucosa, tenderness at the site of fracture and crepitus can also be elicited.

Diagnosis is possible by imaging.

Imaging:

Closed methods - Interdental wiring and intermaxillary fixation are useful.

Open method - Fracture site is exposed and fragments can be fixed by direct interosseous wiring. This is further strengthened by a wire tied in a figure of eight fixation. Currently compression plates can be used for fixation. If compression plates are used, prolonged immobilization is not needed.

Condylar fractures can also be treated by intermaxillary fixation with arch bars and rubber bands. Sometimes open reduction with interosseous wiring can help. Immobilization of mandbile beyond 3 weeks in condylar fractures can cause ankylosis of the temporomandibualr joints.